A new study connects the black hole’s famous ring of light to a compact region that marks the likely base of the jet, bringing scientists closer to understanding how black holes power some of the brightest beacons in the universe.

Recent News

Magnetic Superhighways Discovered in a Starburst Galaxy’s Winds

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international team of astronomers has mapped a magnetic highway driving a powerful galactic wind into the nearby galaxy merger of Arp 220, revealing for the first time that its fast, molecular outflows are strongly magnetized and likely helping to drive metals, dust, and cosmic rays into the space around the galaxy.

Making Scientific Breakthroughs Possible in 2025

2025 was an incredibly productive year for AUI, marked by significant advances across astronomy, energy, advanced therapeutics, and STEM education and workforce development.

Jansky @90: The Origins of a New Window on the Universe

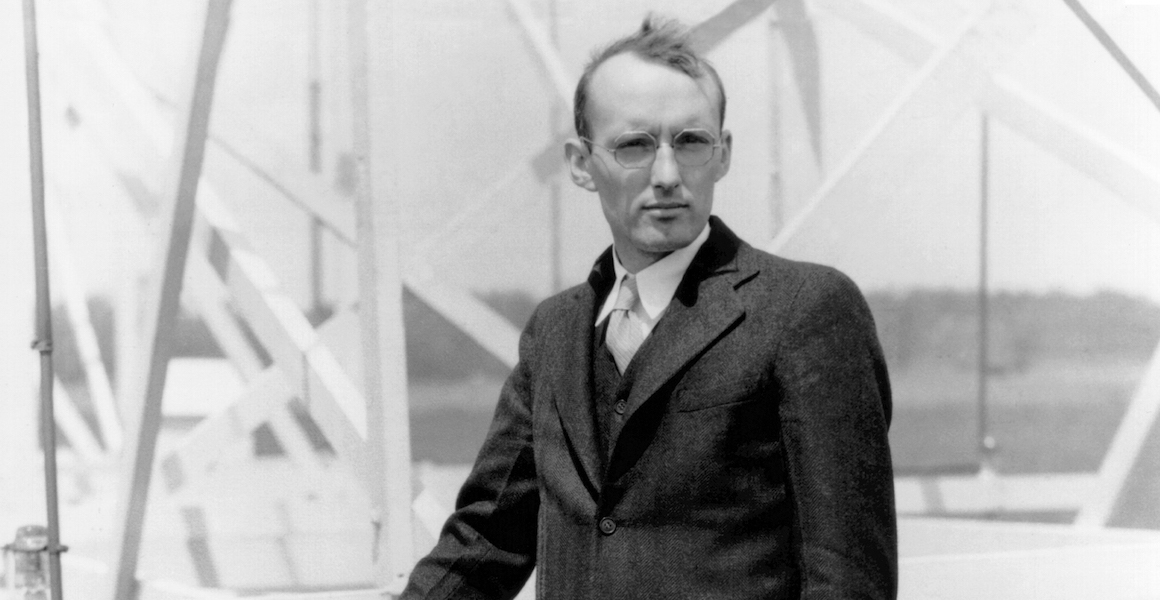

Photo Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF

Note: This article is a collaborative work of Ken Kellermann, Ellen Bouton, Heather Cole, and Jeff Hellerman.

Before 1933, all we knew about the Universe came from observations made through the limited visual region of the electromagnetic spectrum. That all changed in large part thanks to Karl Jansky.

Jansky did not set out to develop a new field of astronomy. While working for AT&T Bell Laboratories, Jansky was assigned the task of understanding the source of interference to transatlantic telephone communications. Using a 21 MHz rotating array, over a period of three years, Jansky meticulously traced the origin of the noise to the center of the Milky Way.

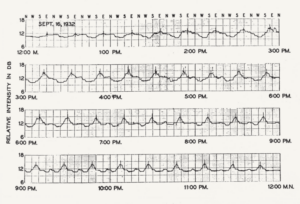

Most of Karl Jansky’s records and notes at Bell Labs were either lost or destroyed. One of the few remaining records of his observations is this series of scans made on September 16, 1932, which he published in the Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers, Vol. 21, 1387 (1933). The peaks in his recorder tracings show the increased noise when his antenna beam crossed the Milky Way three times an hour.

The graph of Jansky’s early observations. Credit: Karl Jansky

On 18 January 1932, Karl Jansky wrote:

“The peculiar thing about this static is that the direction from which it comes changes gradualy [sic] and what is most interesting always comes from a direction that is the same or very nearly the same as the direction the sun is from the antenna.”

But by March, Jansky became puzzled because, during January and February, the direction of his hiss noise had gradually shifted so that now it no longer coincided with the Sun.

Distracted by his other Laboratory responsibilities, nearly a year went by before Jansky was able to return to his “star noise.” On 15 February 1933, he wrote to his father…

“My records show that the hiss type static mentioned in my previous paper comes, not from the sun as I suggested in that paper, but from a direction fixed in space. The evidence I now have is very conclusive and, I think, very startling.”

On 27 April 1933, Jansky made a short 12-minute presentation at the meeting of the US National Committee for the International Union for Radio Science (URSI). Jansky’s Bell Labs boss, Harald Friis, pressured Jansky not to make an extraordinary claim, so the paper had the innocuous title, A Note on Hiss Type Atmospheric Noise, which he wrote to his father, “meant nothing to anybody.” The following week, the 5 May 1933 edition of The New York Times carried the headline, Radio Waves from the Centre of the Galaxy.

Outside of his work, Jansky was an enthusiastic athlete and excelled in many sports and pastimes. He starred at right-wing on the University of Wisconsin Badgers Ice Hockey team. He had the highest batting average as the catcher on the Bell Labs softball team and was the table tennis champion of New Jersey using a homemade racket. He enjoyed golf, tennis, bowling, sailing, and skiing, and he was a competitive bridge player and passionate birder.

Replica of the antenna used by Karl G. Jansky at Green Bank Observatory. Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF

Following the publication of his discovery of cosmic radio emission, Jansky had only limited opportunity to continue this research, as his time was increasingly taken by other Bell Labs priorities. In 1949 Jansky was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physics but this was before the significance of his work was widely appreciated. Nevertheless, his legacy has been recognized in many ways.

In 1973 IAU General Assembly resolved that the name ‘Jansky,’ abbreviated ‘Jy’ be adopted as the unit of flux density in radio astronomy and that this unit, equal to 10-26 Wm-2Hz-1, be incorporated into the international system of physical units. Although originally intended to define only the unit of radio flux density, the Jansky has become the de facto unit for measurements throughout the electromagnetic spectrum

The annual Karl Jansky Lectures were established by the trustees of AUI and NRAO to recognize outstanding contributions to the advancement of radio astronomy.

For more information about Karl Jansky and the history of radio astronomy, check out the NRAO/AUI Archives.

This news article was originally published on the NRAO website on April 27, 2023.

Recent News

New Event Horizon Telescope Results Trace M87 Jet Back to Its Black Hole

A new study connects the black hole’s famous ring of light to a compact region that marks the likely base of the jet, bringing scientists closer to understanding how black holes power some of the brightest beacons in the universe.

Magnetic Superhighways Discovered in a Starburst Galaxy’s Winds

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international team of astronomers has mapped a magnetic highway driving a powerful galactic wind into the nearby galaxy merger of Arp 220, revealing for the first time that its fast, molecular outflows are strongly magnetized and likely helping to drive metals, dust, and cosmic rays into the space around the galaxy.

Making Scientific Breakthroughs Possible in 2025

2025 was an incredibly productive year for AUI, marked by significant advances across astronomy, energy, advanced therapeutics, and STEM education and workforce development.