A new study connects the black hole’s famous ring of light to a compact region that marks the likely base of the jet, bringing scientists closer to understanding how black holes power some of the brightest beacons in the universe.

Recent News

Magnetic Superhighways Discovered in a Starburst Galaxy’s Winds

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international team of astronomers has mapped a magnetic highway driving a powerful galactic wind into the nearby galaxy merger of Arp 220, revealing for the first time that its fast, molecular outflows are strongly magnetized and likely helping to drive metals, dust, and cosmic rays into the space around the galaxy.

Making Scientific Breakthroughs Possible in 2025

2025 was an incredibly productive year for AUI, marked by significant advances across astronomy, energy, advanced therapeutics, and STEM education and workforce development.

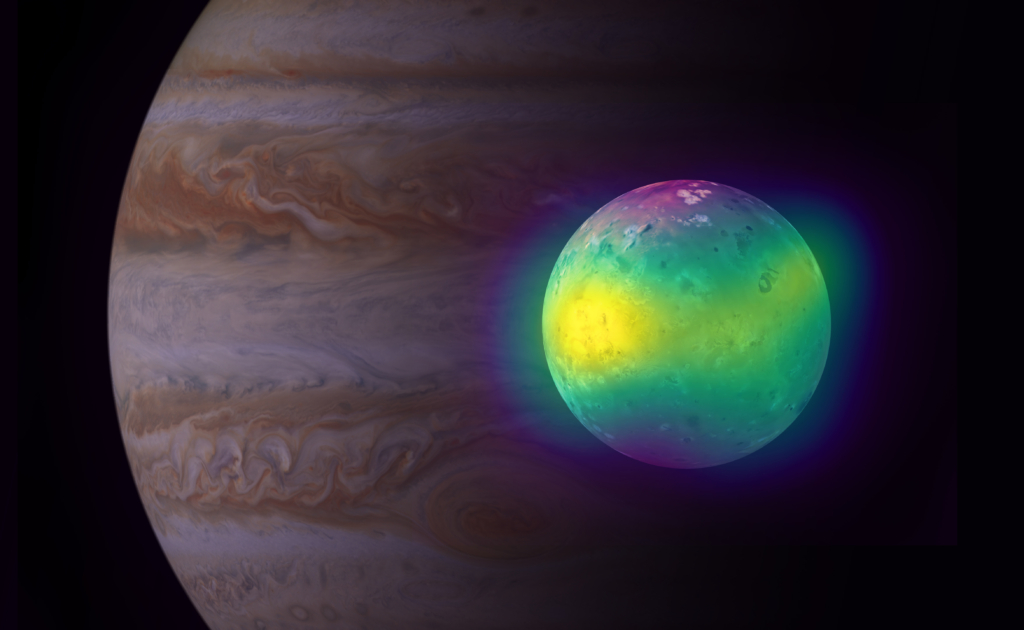

ALMA Shows Volcanic Impact on Io’s Atmosphere

New radio images from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA)

show for the first time the direct effect of volcanic activity on the atmosphere of Jupiter’s moon Io.

Io is the most volcanically active moon in our solar system. It hosts more than 400 active volcanoes, spewing out sulfur gases that give Io its yellow-white-orange-red colors when they freeze out on its surface.

Although it is extremely thin – about a billion times thinner than Earth’s atmosphere – Io has an atmosphere that can teach us about Io’s volcanic activity and provide us a window into the exotic moon’s interior and what is happening below its colorful crust.

Previous research has shown that Io’s atmosphere is dominated by sulfur dioxide gas, ultimately sourced from volcanic activity. “However, it is not known which process drives the dynamics in Io’s atmosphere,” said Imke de Pater of the University of California, Berkeley. “Is it volcanic activity, or gas that has sublimated (transitioned from solid to gaseous state) from the icy surface when Io is in sunlight?“

To distinguish between the different processes that give rise to Io’s atmosphere, a team of astronomers used ALMA to make snapshots of the moon when it passed in and out of Jupiter’s shadow (they call this an “eclipse”).

“When Io passes into Jupiter’s shadow, and is out of direct sunlight, it is too cold for sulfur dioxide gas, and it condenses onto Io’s surface. During that time we can only see volcanically-sourced sulfur dioxide. We can therefore see exactly how much of the atmosphere is impacted by volcanic activity,” explained Statia Luszcz-Cook from Columbia University, New York.

Thanks to ALMA’s exquisite resolution and sensitivity, the astronomers could, for the first time, clearly see the plumes of sulfur dioxide (SO2) and sulfur monoxide (SO) rise up from the volcanoes. Based on the snapshots, they calculated that active volcanoes directly produce 30-50 percent of Io’s atmosphere.

The ALMA images also showed a third gas coming out of volcanoes: potassium chloride (KCl). “We see KCl in volcanic regions where we do not see SO2 or SO,” said Luszcz-Cook. “This is strong evidence that the magma reservoirs are different under different volcanoes.”

Io is volcanically active due to a process called tidal heating. Io orbits Jupiter in an orbit that is not quite circular and, like our Moon always faces the same side of Earth, so does the same side of Io always face Jupiter. The gravitational pull of Jupiter’s other moons Europa and Ganymede causes tremendous amounts of internal friction and heat, giving rise to volcanoes such as Loki Patera, which spans more than 200 kilometers (124 miles) across. “By studying Io’s atmosphere and volcanic activity we learn more about not only the volcanoes themselves, but also the tidal heating process and Io’s interior,” added Luszcz-Cook.

A big unknown remains the temperature in Io’s lower atmosphere. In future research, the astronomers hope to measure this with ALMA. “To measure the temperature of Io’s atmosphere, we need to obtain a higher resolution in our observations, which requires that we observe the moon for a longer period of time. We can only do this when Io is in sunlight since it does not spend much time in eclipse,” said de Pater. “During such an observation, Io will rotate by tens of degrees. We will need to apply software that helps us make un-smeared images. We have done this previously with radio images of Jupiter made with ALMA and the Very Large Array (VLA).”

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

# # #

Media contact:

Iris Nijman

NRAO News and Public Information Manager

[email protected]

Imke de Pater and Statia Luszcz-Cook worked with Patricio Rojo of the Universidad de Chile, Erin Redwing of the University of California, Berkeley, Katherine de Kleer of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), and Arielle Moullet of SOFIA/USRA in California.

This research titled “ALMA Observations of Io Going into and Coming out of Eclipse” has been accepted for publication in The Planetary Science Journal. Preprint: https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.07729

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

This news article was originally published on the NRAO website on October 21, 2020.

Recent News

New Event Horizon Telescope Results Trace M87 Jet Back to Its Black Hole

A new study connects the black hole’s famous ring of light to a compact region that marks the likely base of the jet, bringing scientists closer to understanding how black holes power some of the brightest beacons in the universe.

Magnetic Superhighways Discovered in a Starburst Galaxy’s Winds

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international team of astronomers has mapped a magnetic highway driving a powerful galactic wind into the nearby galaxy merger of Arp 220, revealing for the first time that its fast, molecular outflows are strongly magnetized and likely helping to drive metals, dust, and cosmic rays into the space around the galaxy.

Making Scientific Breakthroughs Possible in 2025

2025 was an incredibly productive year for AUI, marked by significant advances across astronomy, energy, advanced therapeutics, and STEM education and workforce development.