Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have discovered that some of the most massive stars in our galaxy are emitting unbelievably tiny grains of carbon dust—dust that one day could form future stars and planets.

Recent News

ALMA Creates Largest-Ever Image of the Milky Way’s Core

The new survey—known as the ALMA CMZ Exploration Survey (ACES)—maps more than 650 light-years across the Central Molecular Zone, the extreme environment that surrounds our galaxy’s supermassive black hole.

Mission Patagonia Welcomes Its 2026 Nature Guardians

A small cohort of educators, scientists and environmental leaders will embark March 3-14 to the southern edge of the world for Mission Patagonia, an immersive outdoor environmental education experience designed to foster deep connection to place, people and planet.

How Radio Astronomy Sees Magnetic Fields

Many objects in the Universe have magnetic fields. Planets such as Earth and Jupiter, the Sun and other stars, even galaxies billions of light years away. But these magnetic fields don’t typically emit light astronomers can see, not even in radio. So how do astronomers study the magnetic fields of distant stars and galaxies?

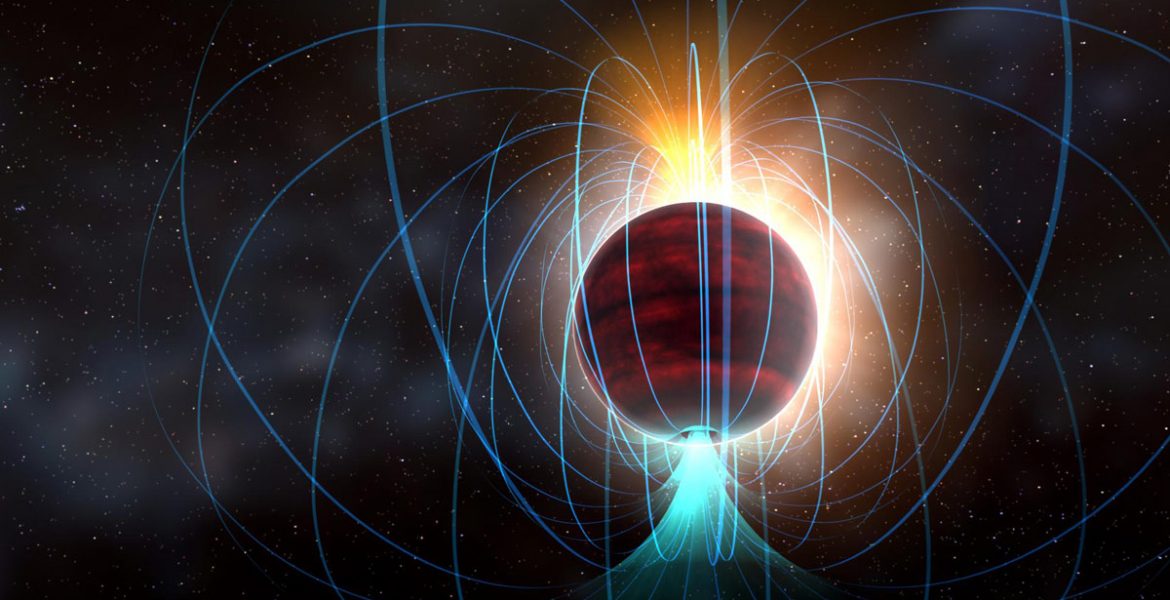

Although magnetic fields don’t emit light, charged particles moving in these magnetic fields often do. For example, aurora on Earth are caused by charged particles from the solar wind that are captured by Earth’s magnetic field. They spiral along the magnetic field lines until they strike our atmosphere near the north and south magnetic poles, which can create both visible and radio light. We can see the aurora on Earth and Jupiter as a beautiful curtain of colors. Astronomers have even observed the radio glow of the aurora of a brown dwarf.

When magnetic fields are extremely strong, charged particles caught in these fields can be accelerated to incredible speeds. As they accelerate around the magnetic field, the charges can emit light directly. It’s known as synchrotron radiation, and it’s often seen coming from the heated accretion disks of black holes. Astronomers can use synchrotron radiation to measure how fast the charges are moving, and how strong the magnetic field is. It has helped us understand how black holes can tear apart and consume stars and also lets astronomers determine the size of distant black hole.

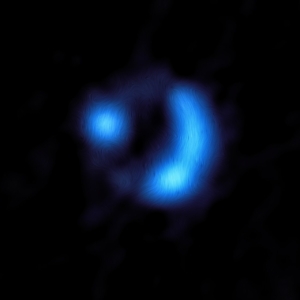

The magnetic field in the distant 9io9 galaxy, as captured by ALMA. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/J. Geach et al.

Astronomers can also map weak magnetic fields. The magnetic field of the Milky Way isn’t as strong as Earth’s, but it permeates our entire galaxy. Our galaxy is filled with charged particles in the form of ionized interstellar gas. This ionized gas doesn’t emit much light on its own, but it does affect light passing through it, particularly polarized light such as that emitted by pulsars. When polarized light passes through an ionized gas, its orientation rotates. The amount the polarization rotates depends on the frequency of the light. By comparing the polarization of pulsar light at different frequencies, astronomers can map the distribution of ionized gas in the galaxy. And since this gas aligns with the galactic magnetic field, they can map the field.

We can even measure the magnetic field of a galaxy billions of light-years away. Recently the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) measured the magnetic field of a galaxy so distant its light took 11 billion years to reach us. This galaxy is particularly dusty, so ALMA observed light reflected and emitted by this dust. This light is polarized along the orientation of the dust grains, and since dust grains tend to align along magnetic field lines, astronomers could use this to map the galaxy’s magnetic field. It is the most distant galaxy known to have a magnetic field.

Astronomers don’t always need to see something to know that it’s there. They just need to see the effect they have on things they can see. From dark matter and dark energy to black holes and magnetic fields, radio astronomy helps us bring these invisible things to light.

This news article was originally published on NRAO website on September 21, 2023.

Recent News

A Quintillion-to-One: Giant Stars, Tiny Dust

Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have discovered that some of the most massive stars in our galaxy are emitting unbelievably tiny grains of carbon dust—dust that one day could form future stars and planets.

ALMA Creates Largest-Ever Image of the Milky Way’s Core

The new survey—known as the ALMA CMZ Exploration Survey (ACES)—maps more than 650 light-years across the Central Molecular Zone, the extreme environment that surrounds our galaxy’s supermassive black hole.

Mission Patagonia Welcomes Its 2026 Nature Guardians

A small cohort of educators, scientists and environmental leaders will embark March 3-14 to the southern edge of the world for Mission Patagonia, an immersive outdoor environmental education experience designed to foster deep connection to place, people and planet.