Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have discovered that some of the most massive stars in our galaxy are emitting unbelievably tiny grains of carbon dust—dust that one day could form future stars and planets.

Recent News

ALMA Creates Largest-Ever Image of the Milky Way’s Core

The new survey—known as the ALMA CMZ Exploration Survey (ACES)—maps more than 650 light-years across the Central Molecular Zone, the extreme environment that surrounds our galaxy’s supermassive black hole.

Mission Patagonia Welcomes Its 2026 Nature Guardians

A small cohort of educators, scientists and environmental leaders will embark March 3-14 to the southern edge of the world for Mission Patagonia, an immersive outdoor environmental education experience designed to foster deep connection to place, people and planet.

ALMA Devours Cosmic ‘Hamburger,’ Reveals Potential for Giant Planet Formation

New images of GoHam give astronomers a rare and supersized model to test how disks evolve and form planets

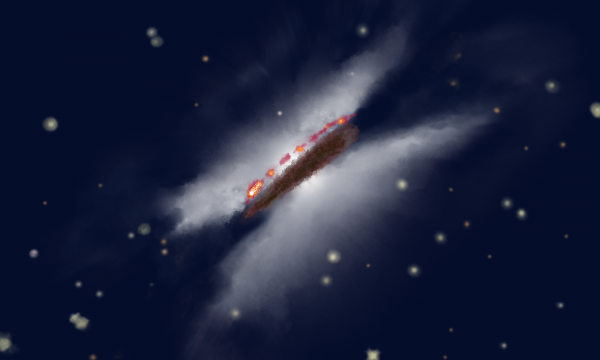

Have you ever found something unexpected in your hamburger? Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) were surprised to discover the very earliest phases of giant planet formation between the dense layers of gas and dust in the “Gomez’s Hamburger” system, referred to as GoHam. This research, currently in preparation for publication, was presented at a press conference at the American Astronomical Society’s annual meeting this January.

Astronomers are able to observe the stacked layers of GoHam’s giant disk of gas and dust, as they rotate around a young star, at an almost edge-on orientation. This gives them a direct view of its vertical structure, something that’s much harder to see in most other disks. Thanks to ALMA observations at millimeter wavelengths, scientists can clearly map the location of the millimeter-sized dust grains, and several different gas-phase molecules, which have arranged themselves in the distinct layers.

These gases include two forms of carbon monoxide as well as the sulfur-bearing molecules CS and SO. The lightest gas (12CO) sits highest above the midplane, while the 13CO sits a bit lower, and the CS lies closest to the midplane, behaving how astronomers would expect, following their understanding of how disks stratify with height. The millimeter dust layer itself is relatively thin and concentrated in the midplane, while the gas extends far above and below, showing just how “puffed up” the gaseous part of the disk is compared to the larger solids.

GoHam is a supersized order: the disk is enormous (and massive) with its 12CO gas stretching out to almost 1,000 astronomical units in radius and reaching vertical heights of several 100s of astronomical units, making it one of the largest known planet‑forming disks. The total dust mass is estimated to be many times higher than in typical disks around similar stars, which means GoHam has huge potential to build giant planets and possibly a future multi-planet system.

This is not a perfect burger. GoHam’s millimeter dust is lopsided north–south: one side of the disk has a more extended and brighter dust emission, due to a vortex or large‑scale disturbance that could help trap solids, providing more food for planet formation. Faint, extended, and wispy carbon monoxide emission appears in the northern part of the disk and at large distances, consistent with a “photoevaporative wind” in which starlight is slowly blowing gas off the disk into space. The team also found an unusual, one‑sided arc of sulfur monoxide (SO) emission just outside the bright dust on only one side of the disk, but with kinematics that still follow the disk’s rotation. This SO arc lines up with a previously-identified dense clump called “GoHam b,” thought to be material collapsing under its own gravity and possibly representing one of the earliest observable stages of a massive, wide‑orbit planet forming in the outer disk.

So how does a fast food order impact astronomers’ understanding of planet formation? “GoHam gives us a rare and clear view of the vertical and radial structure of a very large, nearly edge‑on disk,” shares Charles Law, an NHFP Sagan Fellow at the University of Virginia and PI on this research. He notes that, “This makes it a benchmark system for testing detailed models of how disks evolve and form planets. The combination of extreme disk size, strong asymmetries, winds, and potential planet formation makes it the perfect laboratory for understanding how giant planets can form far from their star, and how their presence reshapes the surrounding gas and dust.”

About ALMA

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international astronomy facility, is a partnership of the European Southern Observatory (ESO), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) of Japan in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. ALMA is funded by ESO on behalf of its Member States, by NSF in cooperation with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) and the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) in Taiwan and by NINS in cooperation with the Academia Sinica (AS) in Taiwan and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI).

ALMA construction and operations are led by ESO on behalf of its Member States; by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), managed by Associated Universities, Inc. (AUI), on behalf of North America; and by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) on behalf of East Asia. The Joint ALMA Observatory (JAO) provides the unified leadership and management of the construction, commissioning and operation of ALMA.

This news article was originally published on the NRAO website on January 5, 2026.

Recent News

A Quintillion-to-One: Giant Stars, Tiny Dust

Astronomers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have discovered that some of the most massive stars in our galaxy are emitting unbelievably tiny grains of carbon dust—dust that one day could form future stars and planets.

ALMA Creates Largest-Ever Image of the Milky Way’s Core

The new survey—known as the ALMA CMZ Exploration Survey (ACES)—maps more than 650 light-years across the Central Molecular Zone, the extreme environment that surrounds our galaxy’s supermassive black hole.

Mission Patagonia Welcomes Its 2026 Nature Guardians

A small cohort of educators, scientists and environmental leaders will embark March 3-14 to the southern edge of the world for Mission Patagonia, an immersive outdoor environmental education experience designed to foster deep connection to place, people and planet.