New research reveals that 3I/ATLAS is packed with an unusually large amount of the organic molecule methanol – more than almost all known comets in our own solar system.

-

29 May 2016

- From the section Latin America & Caribbean

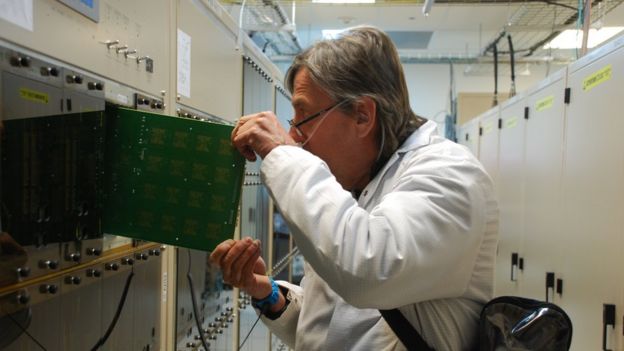

On a bitterly cold afternoon, a small team of engineers moves slowly across Chile’s Chajnantor plateau.

Bundled up against the biting wind, they stop under one of the dozens of giant telescopic dishes scattered across the moon-like landscape.

They unfold a stepladder and clamber up into the back of the dish to carry out routine maintenance.

Each man carries oxygen. At over 5,000m (16,400ft) above sea level, the air here is so thin it is difficult to breathe.

Flurries of snow blow across the plateau. The temperature is -5C, with a wind chill factor of -19C.

‘Giant chess board’

This is Alma, the most powerful radio telescope in the world and one of the most extraordinary places in Chile.

Alma telescope

- Single telescope of revolutionary design, composed of 66 high-precision antennas located at 5,000m altitude on the Chajnantor plateau

- Largest astronomical project in existence

- Inaugurated in March 2013

- Alma is an international partnership between Chile and European, US, Canadian, Japanese, Taiwanese and Korean space and scientific organisations

Perched in the Andes mountains, close to the borders with Argentina and Bolivia, it consists of 66 dishes, or antennas, of up to 12m in diameter.

The dishes can be moved across the plateau like pieces on a giant chess board. Each one weighs 100 tonnes.

The engineers use two massive yellow trucks to haul them into place.

Sometimes the dishes are placed right next to each other. At other times they are up to 15km apart.

Their positioning determines which part of the universe they point toward.

The dishes then work in unison, detecting radio waves from outer space. The waves are converted into data by a super-computer, as powerful as three million laptops, and that data is sent to Alma’s operations centre down the mountainside in the relative warmth at 2,900m.

There, astronomers pore over it, using it to expand our knowledge of the universe and to make some remarkable discoveries.

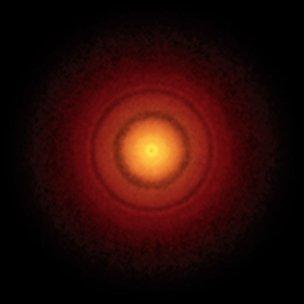

“Just last year we found a site where a disc is being formed around a star, and where planets are being formed,” says Violette Impellizzeri, an operations astronomer at Alma.

“It was so spectacular that even people here at the observatory were blown away by it. It looked like an artist’s painting.”

Dark matter

Ever since the age of Galileo, scientists have used optical telescopes to peer up at the universe, but such telescopes can only detect light waves from a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

They are fine for looking at bright things like stars but not so good for peering into the darker parts of the universe, like the centre of black holes.

That is where Alma (The Atacama Large Millimetre Array) comes into its own.

Scientists recently used it to measure the mass of a supermassive black hole 73 million light years from Earth.

“It’s the first time that’s been done with such accuracy,” Dr Impellizzeri says.

The telescope has also detected sugar molecules in a gas surrounding a young star similar to our Sun. That suggests that solar systems other than our own might be able to support life.

And Alma has been used to look at binary star systems which, unlike our own Solar System, contain two suns rather than one.

No-one knows exactly how planets survive in these binary systems. Logic would suggest that because they orbit two stars rather than one, they should get caught in a dangerous gravitational tug-of-war between the two.

They should get pulled out of orbit, sending them crashing into the stars or flinging them out of their solar system altogether.

But Alma has shown that these planets orbit around double stars surprisingly smoothly.

Astronomers’ paradise

Alma is one of several giant telescopes being built in Chile’s Atacama Desert, which boasts some of the clearest and driest skies in the world.

Altitude is also a factor in choosing to build here. As radio waves reach the Earth, they get distorted by vapour in the atmosphere.

By building in the Andes, engineers can get above some of that moisture.

The Chajnantor plateau is a formidable place to work, but the engineers who do so say it is worth it.

“These antennas can detect molecules in other galaxies. It’s incredible!” says Alma’s project co-ordinator Pablo Carrillo, as he braves the freezing temperatures to make sure the dishes are working properly.

“The technology is state-of-the-art, but because it’s so new it’s susceptible to problems that we haven’t come across before.

“That’s why we’re here – to fix them.”